One adopted person's secret

Spoiler alert: The adopted person in your life might have one, too.

I’m going to tell you a secret. This one is my secret, but it may also be the secret of another adopted person you know. The person who comes to mind when you hear an adopted person speak of grief, loss, longing, and you say something like, “I’m sorry you feel that way. My friend/sibling/spouse/child is adopted and they are fine with it.”

They might be. It is one possibility. But here’s where my secret comes into play. Because my secret might also be their secret.

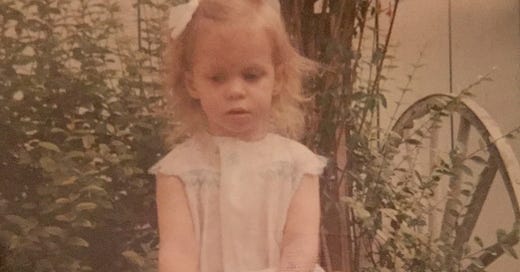

I’m ashamed of the intense longing I feel for my first mother, and of the black hole of grief that’s hidden under layers of coping mechanisms, deflections and denials. The seeds of that shame were planted when I was a young child.

I’ve known I was adopted for as long as I can remember. I don’t remember being told, but I do remember the responses of my adoptive mother when I’d ask questions about it. Questions like:

“Why did my other mother give me away?”

“Is she coming back?”

“When will you give me away?”

Even at 4 or 5 years old, I was aware of my mom’s discomfort. I remember the skin pinching on her forehead, just above the bridge of her nose. I remember her eyes darting away from mine to look at Gremlin (the dog), her dust cloth, the laundry she was folding. And I remember her giving a quick answer, usually “You were very wanted and we waited a long time for you.” Followed by telling me that it was always OK to talk about being adopted at home (though obviously, it wasn’t) but that it wasn’t something we talked about outside the family.

These seeds of shame took root in the fertile soil of disenfranchised grief. They were nourished by the taunts of other kids laughing about how I was such a loser even my “real mother” wouldn’t keep me.

As a young adult, the well-established shame was propped up by the expectations of curious friends or casual acquaintances on the rare occasions the topic of adoption came up. “Have you ever wanted to search for your ‘real mom’?” they’d ask.

If I answered “no,” they were disappointed, and would usually ask why not.

If I answered “yes, I’m thinking about searching,” the next question was almost always: “How does your adoptive mom feel about that?”

Sometimes I’d try adding a qualifier to my response: “Yes, but only to get my medical information.” But we’d still usually end up with the other person asking about my adoptive mother’s feelings. The shame would blossom, and my natural desire to know where I came from withered. Withered, and was hidden, but never died.

It took half a century for the tendrils of that hidden wish to finally find the support they needed to flourish and seek the sunlight of information. I uprooted my life and moved from one coast to the other, seeking a sense of belonging. I felt it in the soothing green landscape and blue waters of the Pacific Northwest.

As I settled in, that sense of belonging seeped into me and I found the courage to push past a feeling of disloyalty and take a home DNA test. As I worked my way through the process of using it to search for my birth family, I found a community of other adopted people. I listened to podcasts, joined online groups and Zoom calls for writing and connecting. The shame began to die back, opening up space for the real me to bask in the sunshine of community and grow. It’s still there, the shame, but it’s small and straggly, and only rarely musters up the strength to blossom.

It’s possible the adopted person you think is just fine is experiencing something like this. It’s possible they are experiencing their own challenges that look nothing like mine. It’s possible they really are just fine. The thing is, you might not be able to tell the difference. Responding to an adopted person’s story in a way that respects their first-hand experience as much as your own second-hand perceptions allows everyone involved to feel the sunlight.

📖 RESOURCE: Adoption Unfiltered, by adoptee Sara Easterly, birth parent Kelsey Vander Vliet Ranyard, and adoptive parent Lori Holden, offers their perspectives as well as insights from interviews with other adoptees, birth parents and adoptive parents.

Yes, it's so nuanced isn't it? I believed I was 'fine' for most of my life, and had made no connection between my sense of loss, grief and lack of belonging and being adopted. It wasn't until I found my bio family that the truth hit me like a ton of bricks. Thanks for this!

beautiful.